Where Have All the English Strikers Gone?

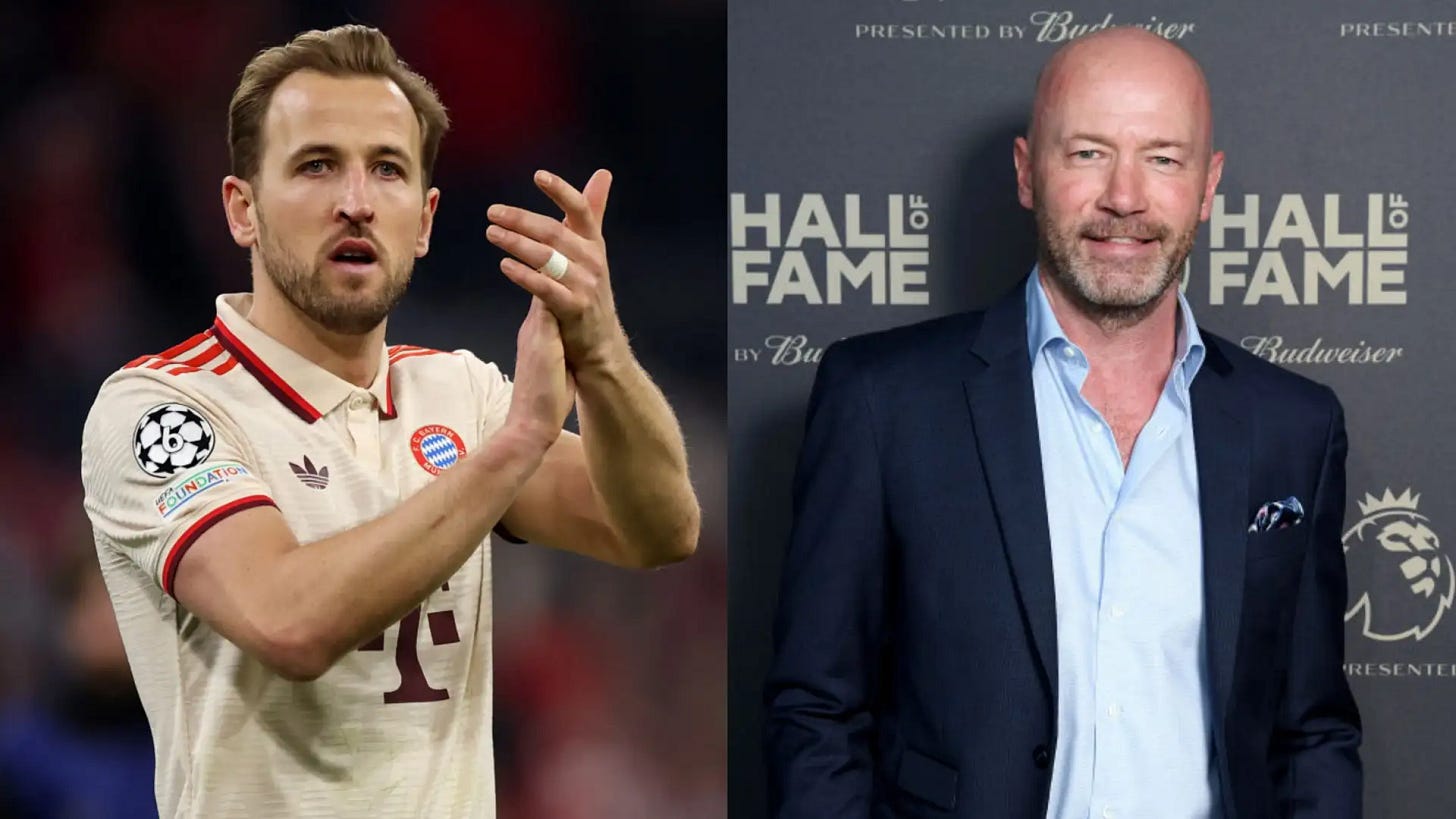

Shearer Set the Standard, Kane Carries What’s Left

Newcastle reportedly want £150 million from Liverpool for Alexander Isak. It sounds like an eye-watering number, but football finance expert Kieran Maguire put that into perspective last week. In a tweet adjusting historic transfers for football inflation, he revealed that Alan Shearer would cost £225 million today. Stan Collymore, £219 million. The post, which also included the likes of Les Ferdinand and Andy Cole, was a reminder of just how rich the 1990s were for English strikers. It inspired me to write this.

There was a time when England had so many top strikers that the manager could afford to leave a 25-goal-a-season forward out of the squad. Now, if you score ten, you’re a contender. The shift has been dramatic, and for fans of a certain age, like me, it’s hard not to feel the loss.

The 1990s were a golden era for English strikers. Alan Shearer was the standout, the definitive number nine. But beneath him was a crop of talent that, in any other era, would have walked into the England team. Robbie Fowler, Ian Wright, Les Ferdinand, Andy Cole, Stan Collymore, Chris Sutton; all of them scoring goals for fun, all of them capable of being the main man.

Today, only one name matches that pedigree: Harry Kane. And he does it in a Bayern Munich shirt. The Premier League, once flooded with English goalscorers, now hosts barely a handful. So what happened? And how did we go from a surplus of options to a solitary figure?

Alan Shearer Was The Standard

If you want to understand how high the bar was set in the 90s, you start with Alan Shearer. He wasn’t just England’s best striker of the decade. He was the benchmark for an entire generation.

The numbers alone are ridiculous. Shearer scored 112 Premier League goals for Blackburn in just 138 appearances. He hit 34 in 42 games in 1994–95, firing Blackburn Rovers to a league title that no one thought they could win. He followed that up with another 31 the next season. Then he moved to Newcastle, his boyhood club, and still managed 148 league goals in black and white.

But Shearer wasn’t just about goals. He was about presence. He could lead the line on his own. He could outmuscle centre-halves, bully them if needed, then bury a half-chance from 25 yards. He was clinical, consistent and cold-blooded. Right foot, left foot, head; it made no difference.

The tragedy is that his prime coincided with an England team that lacked structure, vision and tactical identity. Under Graham Taylor, then Terry Venables, then Glenn Hoddle, Shearer was often the one dependable piece in a puzzle that never quite fit together.

Despite that, he still scored 30 goals for England, including five at Euro 96. He broke a long international goal drought just in time to carry the country through one of its most memorable tournaments. He retired from international football at 29, not because he was past it, but because the weight of expectation was crushing, and he had done enough.

Too Much Talent, Too Little Trust

Behind Shearer was a queue of elite forwards, many of whom would have led the line in a different era. Robbie Fowler was unplayable between 1994 and 1997. Quick, clever and lethal, he scored 25 league goals in three consecutive seasons. He had a sixth sense for space in the box and could finish in ways others hadn’t even considered.

Ian Wright brought energy, charisma and an obsession with scoring. He became Arsenal’s all-time top scorer before Thierry Henry arrived. His numbers were outstanding, but for England, he was often a substitute, used late in games or overlooked altogether. Wright’s international career felt like one long missed opportunity, and you wonder whether managers distrusted his non-league background or his free spirit.

Les Ferdinand had everything. He was strong, quick and brilliant in the air. He scored 24 goals in his first season at Newcastle. In an ideal world, he and Shearer could have formed a terrifying partnership for England. But it was only at club level that we saw it. Internationally, the combinations never clicked.

Andy Cole hit astronomical numbers at Newcastle, then Manchester United, but his relationship with the national team was strained. He only earned 15 caps, partly because of criticism that he needed too many chances to score. But at his best, he had pace, movement and goals to spare.

Chris Sutton and Stan Collymore were dominant at times but inconsistent or difficult to manage. Sutton refused an England B call-up and never played again. Collymore’s talent was real, but his focus wavered. Le Tissier, more of a second striker, had moments of magic but was considered a luxury. Managers couldn’t trust him to press or track back, and so they ignored what he could do with the ball.

Systems Failed the Strikers

Tactics did not help. England spent most of the 90s with no clear attacking identity. Taylor chopped and changed his forwards, treating the role like a rotating experiment. Venables understood balance better, pairing Shearer with Teddy Sheringham to good effect in Euro 96. But even then, Fowler was barely used, and Wright never got his moment.

Hoddle introduced more continental systems, playing Sheringham as a deep-lying striker behind Shearer. It worked in moments but excluded players who relied on space or service. There was no consistency. Players like Fowler and Cole never had a run of games to find their rhythm.

David Platt often scored more goals from midfield than many forwards managed for England. That alone tells you something was broken. With so much firepower in the league, the national team struggled to get the ball into dangerous areas. Creativity was patchy, and chances were scarce.

Foreign Imports Changed the Game

By the end of the decade, the Premier League was changing. Foreign players flooded in. Clubs began signing strikers from across Europe and beyond. Klinsmann, Zola, Bergkamp, Henry and Hasselbaink raised the bar, and managers started to trust imported talent over homegrown options.

That shift had consequences. Young English strikers got fewer chances. Academies started to focus more on midfielders and ball-players. The poacher became unfashionable. The penalty box predator was phased out.

When Shearer retired from England duty in 2000, there was no obvious successor. Owen had emerged and was electric, but he was different. He played off the shoulder and needed a foil. Emile Heskey came in, not as a goal scorer, but as a target man to help Owen thrive. That became the new model, one striker to do the damage, another to do the dirty work.

The days of multiple English strikers pushing each other to new heights were gone.

Harry Kane Stands Alone

Kane is the one true heir to Shearer. He scores every type of goal, leads the line brilliantly and creates chances for others. He is a more refined footballer than Shearer was, more creative perhaps, but less imposing physically. Still, the comparison stands. He is as reliable as they come and carries the burden of expectation like a man built for it.

But who is behind him?

Dominic Calvert-Lewin can’t stay fit. Callum Wilson is consistent but fragile. Ivan Toney is gifted but untested at the highest level. Ollie Watkins works hard and scores goals but still feels raw. There is no Fowler. No Ferdinand. No Wright. Not even a Collymore.

The gap is obvious. Kane plays for Bayern Munich because no English club outside Manchester City could give him the shot at silverware he needed. That speaks volumes.

It Was More Than Nostalgia

People say it is nostalgia, but the numbers back it up. In the 1993–94 Premier League season, five English players scored over 20 league goals. In 2023–24, just one did, and now there are none.

This is not about sentiment. It is about substance. The 90s had strikers who were elite by any standard. They were flawed, sure, but they were relentless. They could win games on their own. They were characters, fighters, match-winners.

Now, we wait and hope. Maybe a new generation will come. Maybe someone will break through. But until then, we watch Kane carry the torch alone and remember a time when England had more strikers than it knew what to do with.