When Christmas Day Belonged to Football

A nostalgic look back at the lost tradition of festive fixtures, how the game quietly stepped away from 25th December, and why television now shapes Christmas football

When Christmas Day Was Matchday, and Football Had to Fit Around Life

There is a particular kind of quiet that arrives on Christmas morning. The kettle clicks, the house settles, and the world, for a few hours at least, seems to agree to slow down.

And yet, not so long ago, football did the exact opposite.

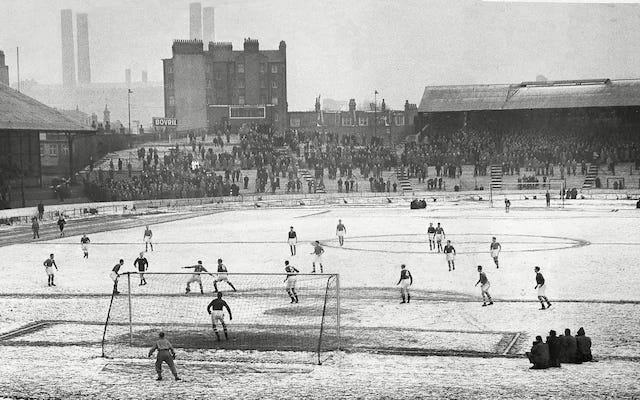

For generations in Britain, Christmas Day was not only a day for family and faith, it was also a day for fixtures. Proper ones too, with league points on the line, heavy pitches under winter skies, and supporters wrapped in scarves that had already seen a decade’s worth of Decembers. The idea feels almost impossible now, like a black and white photograph that has slipped out of its frame. But it was real, and it mattered.

The question is not whether we miss it, because most of us never lived it. The question is what it says about the game we have now, a game that once bent itself around the calendar and now expects the calendar to bend around it.

Why football ever landed on Christmas Day

The roots are surprisingly practical. Christmas Day was a public holiday, travel was more local, and communities were smaller. If you lived a short walk from the ground, you could attend a match and still make it back for dinner, even if dinner was a modest affair compared to the modern spread.

Clubs also leaned into the obvious logic. People were off work, there were fewer competing entertainments, and a match was a communal event that matched the spirit of the day. The festive programme became a tradition: local derbies, familiar opponents, sometimes even the sort of quick turnaround that would make today’s sports science departments faint.

This was also a time when football crowds were a physical expression of town identity. Going to the match was part of who you were. On Christmas Day, it became part of what you did.

The slow fading of a tradition

What tends to disappear in football rarely vanishes overnight. It fades, season by season, decision by decision, until it becomes “the way it is” and we forget there was ever another way.

In England, the full Christmas Day programme began thinning out in the late 1950s. By 1957 it was still largely intact, but by 1958 the top flight card had shrunk dramatically, and by 1959 only a couple of rearranged league fixtures were played on 25th December.

The final English league match played on Christmas Day came later, on 25th December 1965, when Blackpool beat Blackburn Rovers 4–2 at Bloomfield Road, watched by 20,851 supporters who chose football before the second helping of turkey.

That, in its own way, feels like the perfect last scene. Blackpool, a holiday town, leaning into the festive crowd. A derby edge to the fixture. The sense of an era trying to hold on for one more afternoon before time finally calls it.

Scotland held on longer. The last Christmas Day league matches there took place in the 1976–77 season, with St Mirren drawing 2–2 with Clydebank and Alloa beating Cowdenbeath 2–1 on 25 December 1976.

So, what changed?

The shift that mattered most: football stopped being local

Part of the answer is transport, oddly enough.

As travel became easier, Christmas became less local. Families dispersed. People drove, visited, hosted, rotated between relatives. The day filled up in a way it did not always do when communities lived closer together. Christmas Day became less compatible with the idea of thousands heading to the turnstiles.

Players also began to push back. The romance of a Christmas Day match looks different if you are the one missing the morning with your kids, or eating a rushed meal before a bus journey, or reporting for duty while everyone around you gets to be off.

And football, for all its nostalgia, has always been a workplace. The moment players and staff could collectively say, “This is not the day for it,” the tradition was living on borrowed time.

Floodlights, television, and the new centre of gravity

There is another piece that does not get enough attention. Football used to need the holiday to make the schedule work. Once floodlights and midweek football became normal, the sport no longer required Christmas Day to squeeze in a programme.

That shift is important because it quietly flipped the logic. Christmas Day fixtures were not only a tradition, they were a scheduling solution. Once the solution was no longer needed, the tradition became optional, and optional things are usually the first to go.

Television then arrived not as a side character but as the lead.

At first, the fear was not that TV would dominate football, it was that it would damage it. Burnley chairman Bob Lord, one of the most influential voices of his era, argued televised matches would “damage and undermine attendances.”

That line still echoes through the sport in the form of the Saturday 3pm blackout, a rule rooted in the 1960s that restricts live domestic broadcasts in that window to protect matchgoing crowds.

Whether you love the blackout or loathe it, the principle is revealing. Football’s leaders understood, even then, that television did not simply show the game. It shaped behaviour around the game.

Now television decides the festive season

Fast forward to today and the balance of power is obvious.

The festive period no longer feels like a tradition created by communities, it feels like a product designed for audiences. Kick off times are chosen for broadcast slots. Rivalries are packaged for maximum viewing. Even the sense of “Christmas football” is often less about what day it is and more about what the TV schedule says it is.

And it is not that supporters do not enjoy it. Many do. There is something comforting about football during the holidays, a familiar rhythm when work stops and the days blur into each other.

But the trade off is real. The game that once belonged to the streets around the stadium now belongs, in large part, to the broadcasters’ running order.

Players talk about it plainly. Fulham’s Tom Cairney once described having to travel on Christmas night and staying in a hotel, adding, “It wasn’t that glamorous, and you’d rather be doing other things, but it’s your job.”

That is modern football in one quote. The schedule does not pause, it just relocates the inconvenience, from supporters to staff, from Christmas Day itself to Christmas Eve, Boxing Day, or the days wrapped tightly around them.

What we have gained, and what we have lost

We have gained access. We see more football than any generation before us could imagine. We can follow teams home and away, watch highlights instantly, and argue about shape, structure and substitutions in real time with people across the country.

We have also gained a kind of shared national experience. When a big festive fixture lands, it becomes a talking point at tables and in group chats. Even those who claim they are not bothered often know the score before the pudding is served.

But we have lost something too.

We have lost the idea that football fits around life rather than life fitting around football. We have lost the sense that the match is an event you physically commit to, rather than content you consume when the TV says it is on. And we have lost, perhaps most quietly, the local simplicity of it all.

Christmas Day football belonged to a time when the ground was close, the opponent was familiar, and the day could hold both a match and a family meal without tearing itself apart.

That world has gone. It is not coming back, and maybe it should not. Footballers deserve Christmas morning with their families as much as anyone else. Supporters deserve the freedom to choose how they spend the day, without a fixture tugging at them.

Still, it is worth remembering. Not because we want to turn the clock back, but because it reminds us what football used to be.

A game that lived among people, not above them.

And on Christmas Day, of all days, that feels like a thought worth keeping.