Seeing Beyond the Scoreline, Why xG Changes How We Watch Football

A personal look at the rise of expected goals, how it helps, where it fails, and why this stubborn little metric has become part of every supporter’s matchday ritual.

There was a time when all we ever argued about after a match was effort, shape and whether the referee should be allowed near a whistle again. Now, as soon as the full time whistle goes, the numbers arrive. Possession, shots on target, passes completed, and right in the middle of it all sits the modern buzzword of the game: expected goals, xG.

I will be honest, like most people I have been on a journey with it. At first I rolled my eyes. Then I got hooked. Now I sit somewhere in between, trying to use it as a tool rather than a trump card.

What xG Actually Tries To Tell Us

Strip away the mystique and xG is quite simple. Every time a player has a shot, that moment is given a value between zero and one. That number is meant to represent the probability of a goal, based on thousands upon thousands of similar shots from the past.

Think of a penalty. Historically, about three out of four are scored. So a penalty will usually get an xG of around 0.75. A scruffy effort from outside the box with bodies in the way might only be 0.03 or 0.04. A close range chance in front of goal might come in at 0.4 or higher.

Add all those little numbers together over the course of a match and you get a total for each team. That tells you how many goals an average side might have been expected to score from the chances they created. It does not know the name on the back of the shirt. It does not know that the striker has scored in his last five games or that the keeper is having the night of his life. It just knows that from that position, in that situation, players usually do this.

Clubs lean on this heavily now. Recruitment departments look not only at how many goals a forward scores, but whether he is getting into good areas regularly. A player who scores ten from an xG of ten looks very different from one who scores ten from an xG of five. The first is creating a steady flow of decent chances. The second might be living off worldies that will dry up when confidence dips or the wind changes.

Why Managers And Analysts Love It

Inside clubs, xG is a way of stripping emotion out of the story. The scoreboard never lies, but it does not always tell the whole truth either.

You know that feeling when you come away from the ground saying, “If we play like that every week we will be fine” after a defeat? Very often, the xG will agree with you. Your lot might have racked up something close to two expected goals while the opposition scored from a low value effort out of nothing.

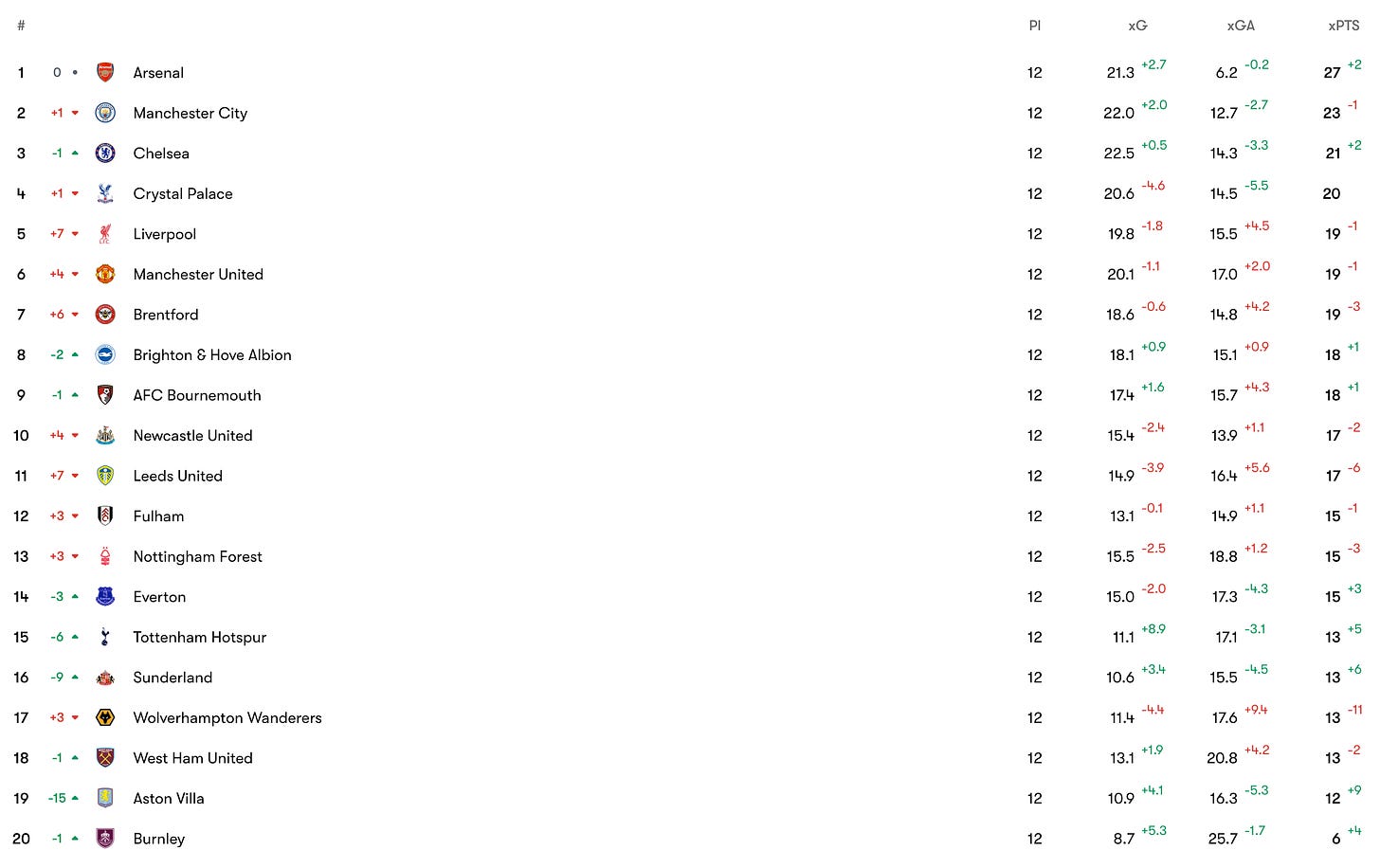

Over a run of ten or fifteen games, those underlying numbers begin to matter more than the odd freak result. If a team is consistently creating good quality chances and not giving much away, the table usually catches up. If their xG is strong and their actual goals are lagging behind, you can reasonably expect a correction at some point, as long as the chance creation remains healthy.

Clubs also use xG related measures. Expected goal difference, that is xG for minus xG against, gives a sense of how a team is controlling matches. Analysts will split xG into open play and set pieces, and strip out penalties to see the true picture of how a side is attacking. For keepers, they will look at xG on shots faced and how much they are over or under that figure to judge shot stopping.

It is not a fancy toy. It is a way of seeing patterns that the naked eye might miss over the grind of a long season.

The Famous Flaws

Of course, xG has plenty of holes in it, and they are worth understanding.

First, it only counts shots. If nobody gets on the end of a wicked cross that flashes across the six yard box, that chance does not exist in xG. The ball sliding past Paul Gascoigne at Wembley in ninety six, studs away from glory, carries no expected goals value at all. Yet anyone who watched it knows how big a moment it was.

Second, not all xG numbers are created in the same way. Different companies build different models, using slightly different inputs. Some will have more angles of a match, some will tag actions in real time while others wait and rewatch every detail. You can see the same game show slightly different totals in different apps. That does not mean one is lying, it just reminds you that these are estimates, not divine truth.

Third, xG does not care who is shooting or who is in goal. A penalty for a nervy centre back is treated the same as one for the most ruthless finisher in Europe. A long range free kick from a specialist is graded like any other effort from that distance. Over time, the best players bend the averages. They turn low value chances into goals more often than the model expects. That is why certain teams appear to “beat” their xG on a regular basis. They have elite talent in the right zones.

Game state twists the numbers as well. Score early and you might protect what you have, rather than chase a second and a third. Fall two behind and you will inevitably take more risks, pile on more shots, and often inflate your xG when the contest is already slipping away. Look at the minute by minute graphs after a match and you will often see the losing side piling up cheap xG late on, while the winning side has already gone into cruise control.

One Game Lies, Fifteen Games Tell The Truth

The biggest mistake supporters make with xG is treating it as a verdict on a single match.

You hear it all the time. “We had higher xG, so we deserved more.” All that really means is that across the ninety minutes, your chances carried a higher combined probability than theirs. It does not account for the quality of finishing or the brilliance of an individual strike. You can score from two half chances at the edge of the box and beat a side who have huffed and puffed without ever really convincing.

Flip it round. One afternoon your team might post a total just above one expected goal from ten or twelve shots, while the opposition score twice from efforts that barely move the needle. On paper, that should not happen often. In a long league season it will happen a fair few times. That is the nature of a low scoring sport.

Stretch the lens across ten or twenty games and you start to see the value of the metric. A side that keeps winning by leathering the ball in from distance will usually feel a chill eventually. A side that keeps missing good chances will usually enjoy a purple patch further down the line. xG does not promise justice, it simply points at what is repeatable and what is not.

Where Tactics And xG Meet

One of the fascinating parts of modern football is how managers try to game the model.

Some teams are built around high quality shots inside the box, with cutbacks, through balls and overloads. Their xG charts are packed with chunky values close to goal. Others lean heavily on set pieces, using long throws, routines from corners and clever blocks to get free headers against disorganised defences. The numbers sometimes underplay these routines, because they treat each shot as a fresh event, when in reality the whole pattern is designed for that very moment.

Then there are sides that are comfortable with low xG shots, because they trust the technique of their players. Quick counters that lead to unopposed efforts from the edge of the area, long range strikes into the top corner, direct free kicks that beat the wall and the keeper. On the spreadsheet, those are not supposed to go in very often. On the pitch, the right player can make a mockery of the averages.

That is why you see some teams sitting much higher in the real table than they would if the league were decided by xG alone. They are either defending better than average in key moments, finishing better than average from distance, or both. The model eventually drags most teams towards par, but there is always room for outliers.

How I Use It As A Supporter

So where does all that leave us, standing on a terrace or slumped on the sofa after a grim defeat on a wet Sunday afternoon?

For me, xG has become part of the post match routine rather than the headline act. I will still trust my eyes first. Did we look organised. Did we create good chances. Did we restrict the opposition. Did the keeper bail us out.

Then I will glance at the numbers. Were we consistently getting into good positions or did we pad the total with a flurry of blocked shots late on. Did the opposition really carve us open or did they score from the only real sight of goal they had. Was our best chance a close range header from a corner that I had almost forgotten about by the time I got home.

Used that way, xG is a conversation starter rather than the end of the argument. It lets you separate the odd freak scoreline from a genuine pattern of concern. It can reassure you that a dry spell in front of goal might pass. It can warn you that a string of wins built on long shots and goalkeeping heroics may not last forever.

The Bottom Line

Expected goals is not going away. Clubs lean on it, broadcasters flash it up on graphics, fans quote it to win arguments in group chats.

The trick is to treat it as an informed estimate, not a law of the game. One match number can mislead. Ten or fifteen will tell you something real. Use it alongside everything else you know about football. Think about game state. Remember it does not see the names or the nerves. Respect the moments that the model misses, like the missed tap in that never became a shot, or the slide at the back post that finished a stud away from glory.

If we do that, xG becomes what it should always have been, a helpful guide that nudges us closer to the truth of how our teams are really playing, rather than a stick to beat people with when the ball hits the post.