Deloitte Money League Exposed: Football’s Rich List Tells Half a Story

Why record revenues are masking deeper truths about power, risk and control

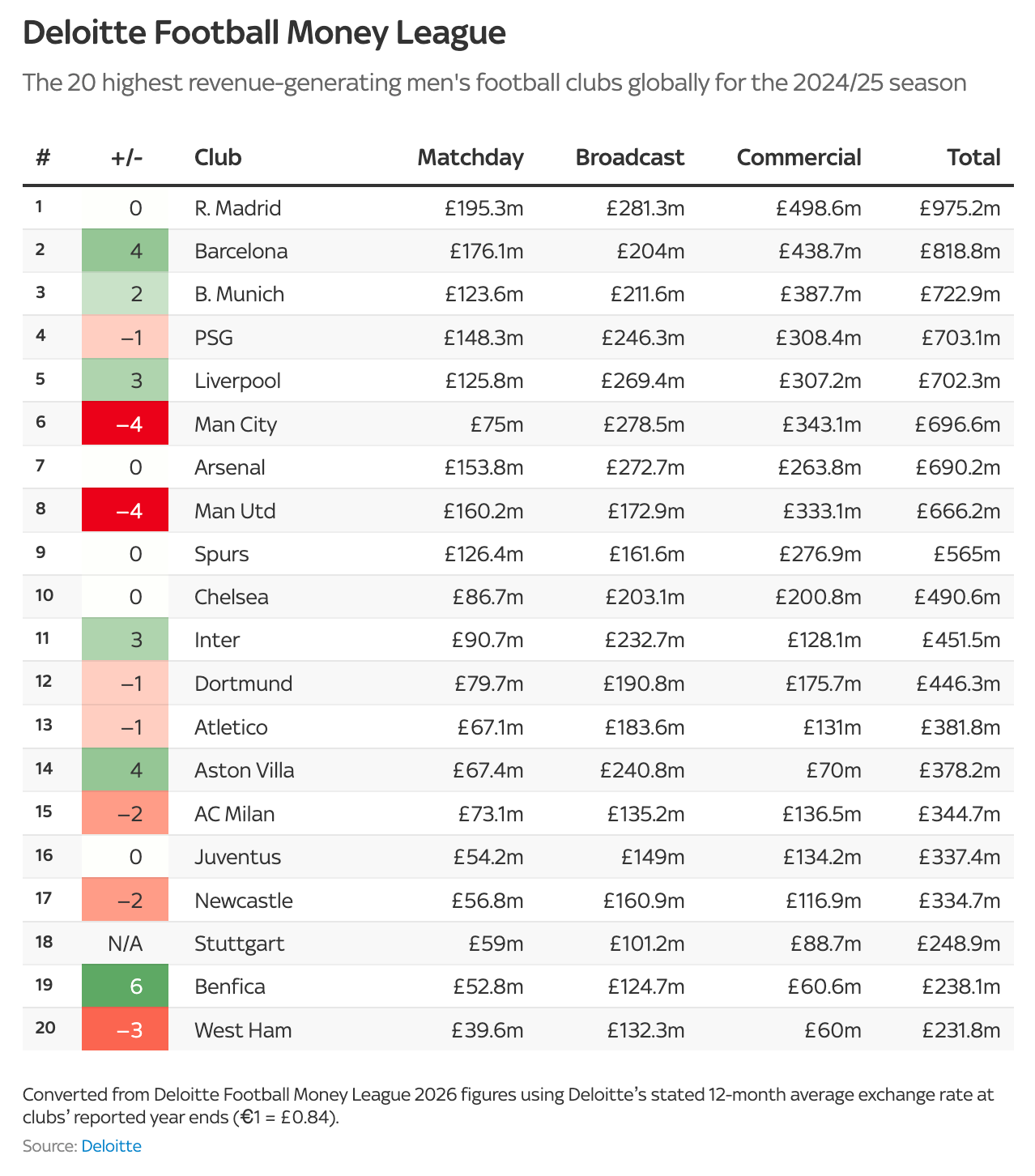

The Deloitte Money League arrives each year dressed as authority. A ledger of winners, a hierarchy of power, a neat arrangement of football’s elite by financial muscle. It is presented as fact, digested as truth, and debated as judgement. Yet the further the numbers climb, the less they seem to explain.

Revenues have never been higher. Combined income across the leading clubs has sailed past previous records, buoyed by expanded competitions, global commercial reach, and stadiums that rarely sleep. On paper, the game looks richer, stronger, and more assured than ever.

On the ground, it feels anything but.

This latest edition of the Money League confirms what many suspected. The gap between income and insight is widening. Revenue dominance is no longer a reliable indicator of good governance, competitive balance, or long-term health. In some cases, it disguises fragility. In others, it rewards behaviour that would raise questions in any other industry.

The list still matters. But it demands far more scepticism than it receives.

Revenue obsession distorts reality

Football has trained itself to worship turnover. Bigger numbers are celebrated as progress, irrespective of how they are achieved or what they cost. The Money League feeds that obsession, ranking clubs by gross income while largely ignoring what is spent to generate it, or what risks sit beneath the surface.

Several of the highest-earning clubs continue to operate on the financial edge. Losses remain commonplace. Debt is normalised. One-off revenue injections are absorbed into headline figures as if they were permanent features rather than temporary fixes. A club can soar up the rankings while remaining structurally vulnerable.

This is not an accident. Revenue is easy to sell. It flatters ambition and reassures investors. Profit, restraint, and sustainability do not.

The danger lies in mistaking size for strength. Clubs that generate extraordinary income often do so because they are compelled to. Wage inflation, transfer fees, and competitive pressure force constant escalation. Standing still is failure. Growth becomes mandatory, not optional.

When revenue growth slows, the consequences arrive quickly. European qualification missed. Broadcast income drops. Commercial projections wobble. The model depends on relentless success, and football success is cyclical by nature.

Yet the Money League freezes this motion into a static image, implying order where volatility rules.

Premier League wealth spreads, power concentrates

Much has been made of the absence of English clubs from the very top of the rankings. It has been framed as decline, as slippage, as a loss of dominance. That interpretation misses the point.

The Premier League remains the wealthiest domestic competition in football. Its strength lies in distribution. Even clubs outside the elite generate revenues that would dwarf historic giants elsewhere. This breadth is not weakness. It is resilience.

However, distribution does not equal competitive freedom.

While income is spread, power remains concentrated. A small group of clubs dominate wage spending, squad depth, and access to elite talent. Revenue may be shared more evenly, but the ability to convert it into sustained success remains skewed.

This creates a strange duality. English clubs populate the upper reaches of the Money League almost by default, yet the very mechanisms designed to regulate spending have hardened existing hierarchies. Financial rules reward those who arrived early, built scale first, or operate with alternative safety nets.

The Premier League is rich, but increasingly rigid.

State-backed models reshape competition

No discussion of modern football finance can avoid the question of ownership. The Money League does not judge source, only outcome. Revenue counts the same regardless of origin, intent, or dependency.

State-backed clubs expose the limits of this neutrality.

When commercial income accelerates beyond what traditional market logic would suggest, suspicion follows. Some view it as innovation, others as a distortion. What is undeniable is the impact. Wage ceilings are pushed higher. Competitive baselines rise. Rivals must either match the spending or accept inferiority.

This does not require illegality to be effective. The mere presence of owners with vast external resources alters behaviour across the league. Risk tolerance increases. Losses feel manageable. Long-term consequences recede.

The Money League records the results, not the causes.

It cannot capture the psychological shift that occurs when competition moves from organic growth to industrial scale. Nor does it account for the regulatory strain that follows, as authorities struggle to police frameworks designed for a different era.

Revenue keeps rising, but trust erodes.

Sustainability question refuses to go away

For all the billions now circulating through football, the same questions return each year. Why do so few clubs generate consistent profit? Why does success demand ever greater spending? Why do financial controls feel both intrusive and ineffective?the

The answers sit between the lines of the Money League.

Football has chosen a model that prioritises scale over balance. Growth over prudence. Prestige over restraint. Revenues climb because they must. Costs follow because they always do. The margin for error shrinks with every new contract signed.

Expanded competitions provide short-term relief, but introduce new dependencies. One poor season can unravel years of planning. A missed qualification becomes a financial event, not a sporting one.

Even wage control, often cited as improving, reflects this tension. Ratios fall not because discipline has improved, but because revenues have surged faster than salaries. Should income plateau, the old pressures will return instantly.

The Money League captures a moment, not a trajectory.

What the Money League ultimately reveals

Strip away the branding, the prestige, the carefully ordered tables, and a simpler truth remains. Modern football has built an economy that demands perpetual acceleration. Those best equipped to accelerate rise. Those who hesitate fall.

Revenue rankings reward momentum, not moderation. They celebrate reach, not responsibility. They tell us who is winning the financial race, but very little about who is running wisely.

This does not make the Money League useless. It makes it incomplete.

Used properly, it is a warning system. A snapshot of incentives. A reflection of what the game currently values. Right now, it values scale, commercial reach, and the ability to absorb risk.

Whether that leads to a healthier future remains uncertain.

Football has never generated more money. It has never looked less convinced of its own stability.

Until the conversation shifts from who earns the most to who survives best, the Money League will continue to impress, provoke, and ultimately mislead.